Localized ocean fertilization is not OIF....It’s vastly better

I have a confession.

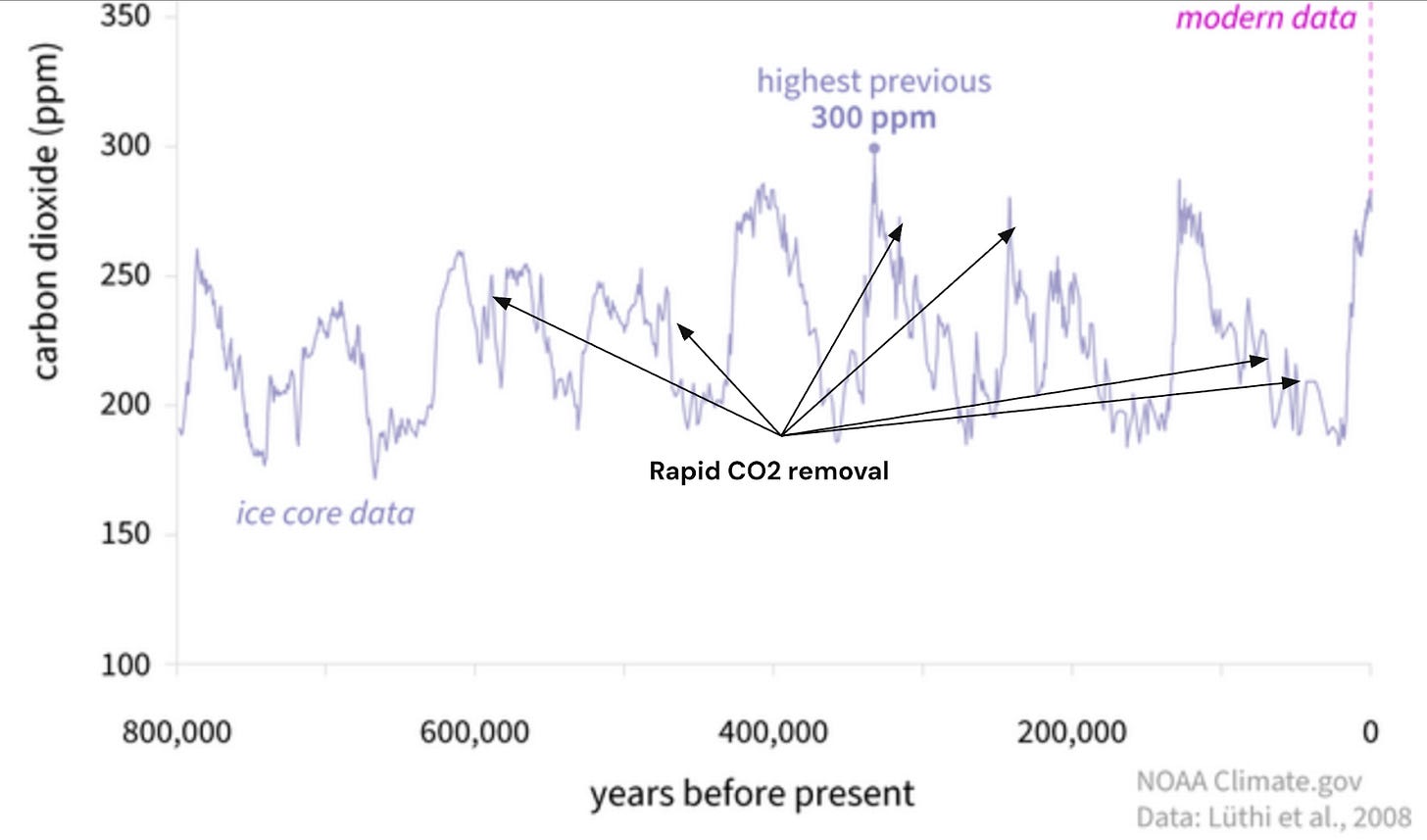

Readers will recall that I’ve discussed ocean iron fertilization (OIF) as our best hope for restoring safe, preindustrial CO2 levels by 2050. I called it the most efficient, affordable, time-tested way to pull down the trillion tons of CO2 we need to remove to give our children a safe climate. It’s the way Nature removes massive amounts of CO2 in the ice age cycle (fig. 1).

You might be aware of OIF’s reputational problems, related to scale and possible side effects. The oceanographic community says that OIF, implemented at full scale, could only bring down 1 to 3 gigatons of CO2 per year. Recall that we have 1,000 gigatons of excess CO2 to clear from the skies, and we need to remove 60 Gt / year to restore safe levels by 2050. Thus 1 or 3 Gt / year is not going to get us far. The scientific literature discusses using the whole ocean to achieve even that (they call it “basinwide.”) Clearly, turning the whole ocean green like pea soup raises environmental alarm bells–making it what I call a non-starter.

Back to my confession: A few weeks ago in a presentation, I named what we’re doing “localized ocean fertilization”, and the experts listening grasped it immediately. Localized ocean fertilization is obviously not basin-wide OIF. For ten years I had been trying to explain that OIF done correctly was safe and effective. LOF is safe and effective. It is not basin-wide OIF. That’s the message.

Please forgive the confusion and allow me to introduce recent analysis that informs our current thinking.

Nature performs localized ocean fertilization (LOF)

Natural phytoplankton blooms stimulated by iron dust are actually localized and usually short-term. Dust storms, wildfires and volcanic eruptions blow dust and ash over small areas of the ocean, not whole basins. The largest of the recurring blooms occurs in the equatorial Atlantic where Sahara dust storms blow into the Caribbean Sea several weeks a year. This area amounts to less than 1% of the ocean. Small blooms related to ocean upwelling and undersea volcanoes are also common.

These blooms are all localized, yet over the period of a few thousand years, they remove many hundreds of gigatons of CO2, as we see in the Antarctic ice-core record in fig. 1.

Fig. 1. CO2 levels over 800,000 years showing repeated removals of 50 to 130 ppm. One ppm corresponds roughly to 10 Gt of CO2. Thus 50 ppm is almost 500 Gt.

Phytoplankton growth leads to sustained CO2 removal only in the right conditions. Mt Pinatubo illuminates these conditions

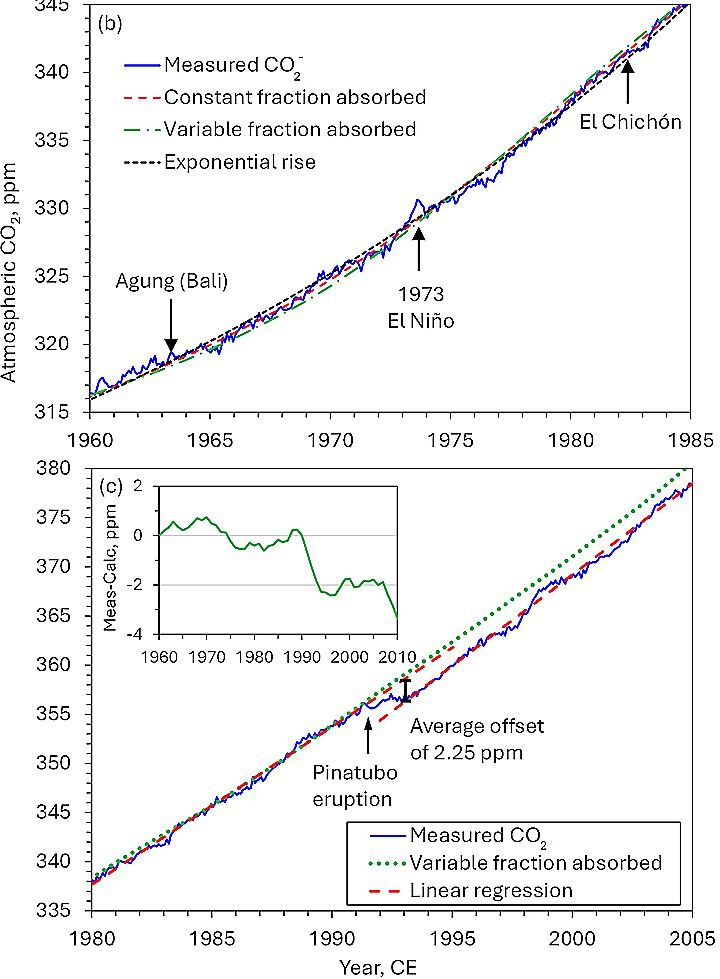

As climate researchers know, the Keeling curve tracks the trajectory of CO2 levels. Interestingly, only once has the Mauna Loa data reflected a sustained pause in the relentless rise of CO2. That “CO2 pause” occurred after the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in 1991. Even more interesting is the magnitude of this anomaly. In about a year, 17.6 gigatons of CO2 were removed—bringing the world near net-zero for the first and only time since measurements at Mauna Loa began.

What happened? I have heard seven hypotheses promoted about what caused the 2.5 ppm reduction in CO2 levels following Pinatubo. Scientists posit a decline in CO2-emitting industry after the fall of the Soviet Union; aerosol-related cooling; aerosol-related light scattering that favored tree growth or understory growth….

Being a physicist, I did the math. For each theory, I calculated how much CO2 could have been removed, and for how long- if it were true.

Only one explanation, first suggested by Sarmiento in 1993, could account for the speed and magnitude of CO2 removal observed–OIF induced phytoplankton growth.

Fig. 2. The lower panel compares actual CO2 levels measured at Mauna Loa (solid blue) with expected CO2 levels (dotted green). The discrepancy indicates long-term removal of 2.25 ppm of CO2. The upper panel shows that two eruptions of similar size and global cooling impact, Agung (1963) and El Chichon (1983) led to no persistent CO2 removal. (Fiekowsky and Burnham, 2025)

Downwelling eddies and nitrogen-fixing bacteria are key

How could an ocean patch constituting 1/1000th of the ocean area possibly have removed more than 17 Gt of CO2 in a year when theory says that the global maximum is less than 3 Gt?

Here’s the two-part LOF hypothesis in a nutshell: when iron dust lands on a downwelling eddy, phytoplankton grow rapidly, and the downward current removes much of the biocarbon before various creatures can eat and metabolize it. When the iron concentration is high enough for several months, nitrogen fixing bacteria multiply and start producing the nitrates needed to keep the phytoplankton growing.

CO2 data following the Mt. Pinatubo eruption in figure 2 indicates that rapid phytoplankton growth continued for over a year after the eruption. This suggests that there was a continuous supply of nitrogen because most iron triggered blooms last a week or two, until the existing nitrogen is depleted. In fact, there appears to have been a rapid bloom after the eruption, visible in figure 2 as the reduction in CO2 immediately after the eruption. This removal died down and CO2 levels resumed their rise again, until several months later when CO2 leveled off for a year.

Coincidently, Trichodesmium, the primary nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria in the tropical ocean, takes several months to multiply into a bloom after sufficient iron is present. This is what we see in fig. 2. Cyanobacteria require 10-20 times higher iron concentration than phytoplankton do. We speculate that some mechanism associated with the downwelling eddy kept iron levels and cyanobacteria growth high for the year of 1992. We don’t know what may have quenched the growth in 1993.

Half a millennium of volcano data doesn’t lie

Not surprisingly, we received pushback on these new ideas. Some scientists insisted that no significant CO2 removal (CDR) actually occurred after Pinatubo. Others continued to attribute the CDR to volcanic aerosols and related cooling.

In the first case, the Mauna Loa data is unambiguous that 17.6 gigatons of CO2 “disappeared” from the atmosphere. This may not show up in the models, but it’s clear in the data.

Second, if aerosols and cooling removed CO2 after Pinatubo, surely they should do the same after other volcanoes similar to Pinatubo. If not, we can forget the aerosol hypothesis.

The CO2 record from Mauna Loa, called the Keeling Curve after the scientist who initiated it, started in 1958. Since then there have been three eruptions big enough to blast vapor out into the stratosphere and cool the planet. Mt. Pinatubo (1991) and two other eruptions, Agung (1963) and El Chichon (1982). The global warming record has distinct half degree dips in those years, but the Keeling curve shows CO2 removal only after Mt. Pinatubo, which is the only one in an ocean region with frequent eddies, seen in the top panel of fig. 2. The other two eruptions, far from eddies, show only brief small dips in CO2, suggesting that ocean life metabolized most of the biocarbon produced.

For confirmation we examined ice core data dating back 500 years and found six more volcanoes large enough to cause cooling similar to Mt. Pinatubo. Only two of these eruptions, in 1580 and in 1815, preceded CO2 levels declines. The ash from those two eruptions also landed in regions with frequent eddies. The other six eruptions weren’t near eddies…and they didn’t impact CO2 levels. This confirms the Pinatubo data and the intuition that eddies greatly increase the amount of CO2 removed after iron levels increase.

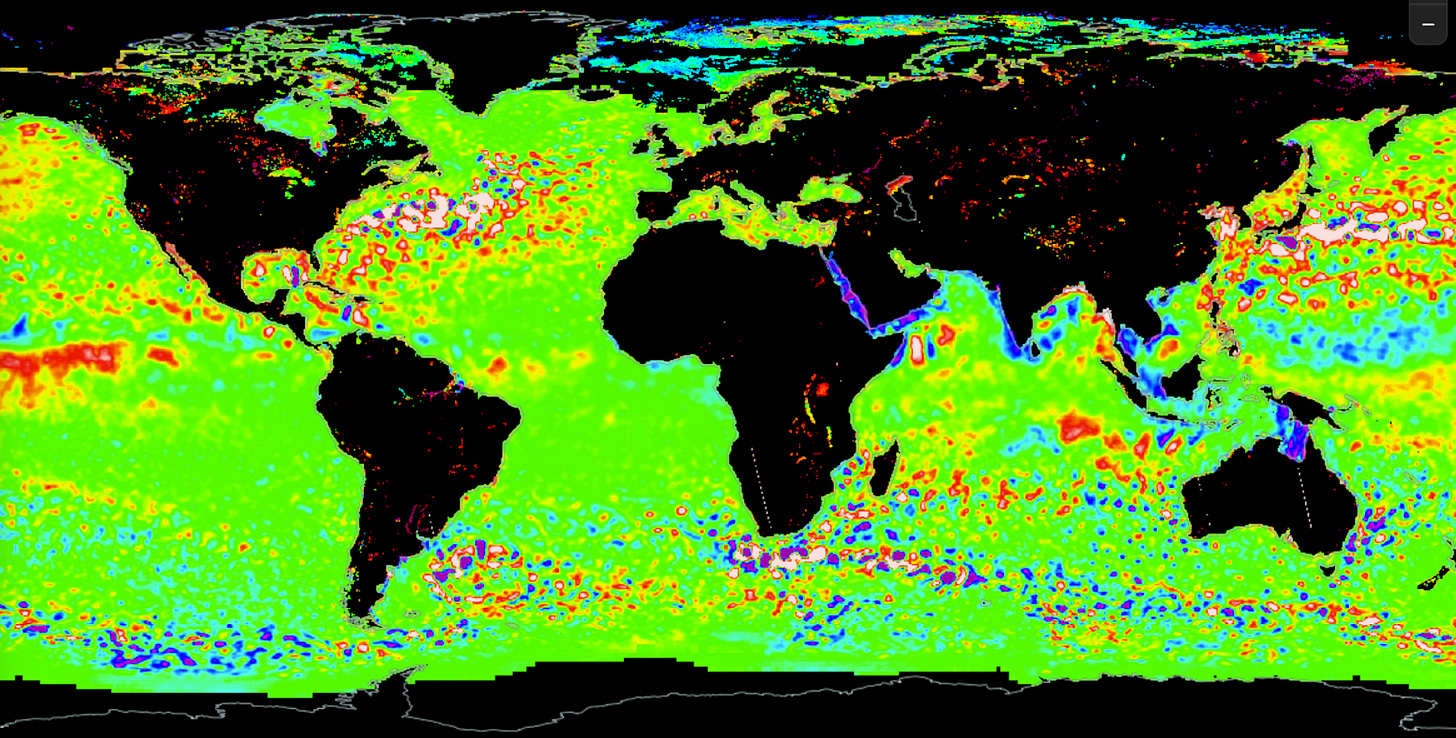

Satellite data confirms the role of downwelling eddies

Next, our team consulted data from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO-2). We developed new software that accurately measures CO2 removal rate, using CO2 and wind data for each location and time.

The satellite data confirms that phytoplankton growth does not necessarily produce long-term CO2 removal. For instance, after the large Tonga eruption of 2022, phytoplankton and chlorophyll levels spiked for a week, as did CO2 removal. Afterwards the chlorophyll faded, and we measured a spike in CO2 emission, presumably from the fish that had come to feast on the lush phytoplankton. There was no local eddy to remove the biocarbon rapidly.

The implications of these findings are enormous. Contemporary modelling suggests that OIF could remove only 1-3 Gt per year, using a whole ocean basin. Yet Keeling curve CO2 data shows removal ten times faster, arguably achieved from only 1/1000 of the ocean area. That means it’s 10,000 times more efficient than models allow.

Downwelling, mesoscale, eddies seem to make the difference. Typically 50 to 400 km in diameter, these whirlpools pull water down much as atmospheric eddies can press air down to form high pressure systems. Several percent of the ocean surface consists of downwelling eddies, and there are vast regions with almost none.

See the header image for a NASA satellite map of ocean eddies. Blue dots represent downwelling eddies; red, upwelling.

They appear to concentrate iron so nitrogen-fixing bacteria thrive, and pull the plankton deep into the ocean before marine animals can metabolize the CO2 back to the air.

For those interested in restoring safe CO2 levels for our children, this is exciting news, showing it’s doable. For those committed to the UN goal of just stabilizing CO2 levels, it means that we can achieve that goal, called net-zero, by 2030, rather than by 2050. This would leave a far healthier planet for future generations.

Advantages of pursuing LOF over conventional OIF

Scale: Because of the tremendous efficiency advantage of LOF, less than one percent of the ocean area has the potential to remove thousands of times more carbon dioxide than “whole-basin” traditional OIF. Net zero could be achieved in 2030.

Permanent sequestration: Downwelling eddies sink biocarbon deep enough (over a kilometer) for the carbon to dissolve into bicarbonate and remain sequestered for hundreds or thousands of years.

Safety: LOF eliminates the concerns expressed about OIF. By definition, it affects only small parcels of the ocean in ways that Nature has done for at least a million years. Any effects, harmful or beneficial would thus be localized, so the area will rapidly revert to pre-intervention status. In addition, few nutrients sink all the way to the seafloor when this occurs in the deep ocean, as it must. As to the concern about “nutrient robbing,” after the biocarbon sinks, the nutrient levels end up essentially unchanged. The phytoplankton ultimately act as a pump that converts CO2 into bicarbonate dissolved in the deep ocean. The nitrogen gets replenished by cyanobacteria and the other minerals dissolve and return to their original concentration in the downwelling current.

Cost: We calculate that due to its efficiency, our advances in measuring CO2, and the low cost of iron, the most abundant element on Earth, intentional LOF would be 100 to 5,000 times less expensive than OIF per ton of CO2 removed. Thus it could operate at full scale for about $1 billion per year–one penny per American per day.

Potential for multi-gigaton CO2 removal: Through careful biomimicry and optimization of LOF, we expect it to be possible to achieve CDR on a multi-gigaton scale. LOF appears to be scalable to 60 Gt CO2 / year by 2030. This is the rate needed to reach net-zero by 2030 and restore historically safe CO2 levels by 2050, should we choose to do that.

Conclusion: Follow the data

The Keeling curve data, OCO-2 images, and the ice-core CO2 record from the last 500 years all support the conclusion that localized ocean fertilization in downwelling eddies is how nature achieves large-scale carbon-dioxide removal.

I started with a confession. I’ll end with a request: Let’s practice distinguishing LOF from full-basin OIF, and advance the safe development of LOF.

Thanks, Peter, for all your work on this. I will share this in my networks. I'm curious how other scientists, studying the possibility of OIF/LIF, are responding to your nuanced findings. One billion dollars a year is a minor blip in some people's/organization's pockets.

The bicarbonate conversion mechanism is what really stands out here. The phytoplankton essentially act as a pump that turns atmospheric CO2 into dissolved bicarbonate at depth, which is way more stable than hoping biocarbon stays sequestered. The Mt. Pinatubo data showing sustained removal for over a year after nitrogen-fixing bacteria kicked in is compelling, makes me wonder why this hasn't gotten more attention in climate circles. Had a professor who always said nature already solved most engineering problems, we just gotta pay attention to the right timescales and locations.